Redistricting: The Road to Reform

In May 2021, Rutgers undergraduate student and John and Ann Holt Endowed Undergraduate Applied Research Fund Awardee Fiona Kniaz completed Redistricting: The Road to Reform, a comprehensive look at the redistricting process. The information below summarizes parts of this report, but the full Eagleton Center on the American Governor report is available for download here.

In May 2021, Rutgers undergraduate student and John and Ann Holt Endowed Undergraduate Applied Research Fund Awardee Fiona Kniaz completed Redistricting: The Road to Reform, a comprehensive look at the redistricting process. The information below summarizes parts of this report, but the full Eagleton Center on the American Governor report is available for download here.

Governors and the Redistricting Process

Now that census numbers are starting to arrive, the next step in the process—the drawing of new districts both at the state legislative and federal congressional levels will take shape. But what role do governors play in the process?

The answer, as with many questions of gubernatorial power, is that it depends on the state. Different states approach the process in a variety of ways, leaving governors to play vastly different roles in drawing and/or approving new district maps. Indeed, some governors play a critical role in the redistricting process, while others have virtually no say at all. Even within the states themselves, a governor may play a different role in apportioning state districts than in creating federal districts.

The sections below break down how each state approaches the redistricting process for both state and federal level districts. They include analysis of the role of each state’s governor, which states provide for special or rare gubernatorial powers, and the current party breakdown in each state (as well as where it could change).

The information was collected and organized by Rutgers undergraduate student Fiona Kniaz (class of 2022) as a research project for the Eagleton Center on the American Governor.

Overview

Virtually no two states redistrict in precisely the same way and no two governors have exactly the same role in the redistricting process. Gubernatorial redistricting powers can range from quite strong, as with Arkansas’s 3-member elected official commission in which one member is the governor, to relatively weak, as in states like California and New Jersey, where a commission not chosen by the governor in any capacity independently draws and approves maps that are not subject to gubernatorial veto.

Each of these systems creates potential politically charged challenges. In states where the legislature or another partisan body is charged with redistricting, for example, the possibility for partisan conflict is high, especially if the majority party of the state legislature differs from that of the governor. However, in states where the state legislature and governor are of the same party—or where checks do not exist to prevent highly partisan maps from being drawn—the possibility for gerrymandered districts is greater.

While state legislatures still draw and approve districts subject to gubernatorial veto in a majority of states, there has been a push in several states since the 2010 Census and subsequent redistricting toward alternate redistricting processes. Many pitfalls remain, however. For example, one possible area for concern is the fact that most states do not have a backup plan if the redistricting body is unable to approve new district maps. This is especially worrisome in states in which the state legislature passes maps as regular legislation, and the possibility for partisan divides between the governor and the state legislature may make it difficult to pass a map on the first try.

| Governors and Redistricting Power |

|

| More than average amount of power | Alaska, Arkansas, Maryland, Missouri, Ohio, Utah, Vermont, Virginia |

| Average amount of power | Alabama, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming |

| Less than average amount of power | Florida, Mississippi, Pennsylvania |

| Virtually no power | Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, New Jersey, North Carolina, Washington |

The chart above categorizes the gubernatorial redistricting powers of every governor in the United States. Most governors simply have veto power over districts drawn by their state’s legislature, which we have classified as an “average” amount of power in the redistricting process. The governors of Arkansas and Ohio arguably have the greatest amount of power of all United States governors, as they sit directly on the committee responsible for redrawing their respective state legislative districts. In Maryland, the governor submits a state legislative redistricting proposal (assisted by a governor-appointed advisory commission), but the legislature can still choose to pass its own proposal. In Alaska and Missouri, the governor makes appointments to a political appointee commission in charge of redistricting and in Utah, Vermont, and Virginia, the governor appoints members to serve on advisory redistricting committees. The Governors of Florida, Mississippi, and Pennsylvania have slightly less than average redistricting powers because they have no role to play in the state redistricting process, but they still have veto power over congressional maps. The governor has no power in the process in some states because they rely on either independent commissions or political appointee commissions in which the governor does not pick any appointees. In the case of North Carolina, the state legislature redraws districts and the governor has no veto power.

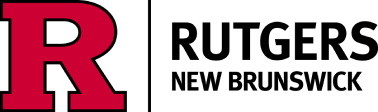

Current Legislative Control (by Party)

As of the 2019 elections, this is the current party map for state legislatures. In 19 states, both houses of the state legislature are controlled by Democrats, compared to 29 states where both houses of the state legislature are controlled by Republicans. In Minnesota, Republicans control the state senate and Democrats control the state house of representatives. Nebraska has a unicameral state legislature that is elected on a nonpartisan basis.

As of the 2019 elections, this is the current party map for state legislatures. In 19 states, both houses of the state legislature are controlled by Democrats, compared to 29 states where both houses of the state legislature are controlled by Republicans. In Minnesota, Republicans control the state senate and Democrats control the state house of representatives. Nebraska has a unicameral state legislature that is elected on a nonpartisan basis.

All states except for Alabama, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, New Jersey, and Virginia will be holding state legislative elections in 2020, so it is very likely that this map will change before redistricting takes place—especially in states where one party narrowly controls one or both houses. In the states that are not holding legislative elections in 2020 (and therefore are unlikely to change control before the redistricting process), Alabama, Mississippi, New Jersey, and Virginia have a state legislature and governorship controlled by the same party, while Louisiana and Maryland have split partisan control.

Drawing State District Lines

In the most common approach to state legislative redistricting—used in 27 states—the legislature draws and passes state legislative redistricting plans as it would regular legislation. (The power of the governor to veto this legislation varies by state; see below). Nine states use a similar process, but with an advisory commission that advises the legislature in drawing the maps. The state legislature then has the final say in approving them. In both scenarios, the plans must be approved with a simple majority vote in each chamber (or, in Nebraska, in the unicameral chamber), except for in Connecticut and Maine, where a 2/3 majority is required for approval.

In the most common approach to state legislative redistricting—used in 27 states—the legislature draws and passes state legislative redistricting plans as it would regular legislation. (The power of the governor to veto this legislation varies by state; see below). Nine states use a similar process, but with an advisory commission that advises the legislature in drawing the maps. The state legislature then has the final say in approving them. In both scenarios, the plans must be approved with a simple majority vote in each chamber (or, in Nebraska, in the unicameral chamber), except for in Connecticut and Maine, where a 2/3 majority is required for approval.

Non-legislative political appointee commissions draw state legislative districts in nine states. These commissions are comprised of members who are directly appointed by elected officials, party leadership, and/or party committees. In some cases, the appointees themselves select a final tie-breaking member. In most of these commissions, the members are not themselves elected officials. Arkansas is the only state to use a politician commission fully comprised of current elected officials. Ohio, meanwhile, uses a hybrid political appointee/politician commission, as the commission is largely appointed except for the governor of Ohio, who sits on the commission as an incumbent politician. Finally, four states use an independent commission comprised of members who cannot be public officials or current lawmakers and who are selected through a screening process conducted by an independent body.

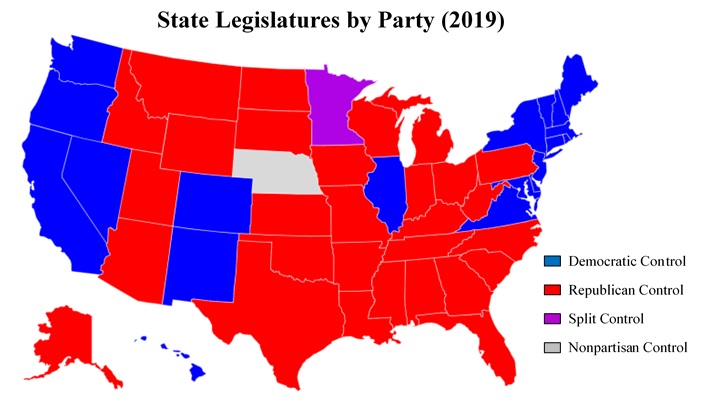

Drawing Congressional Districts

As with state legislative redistricting, most states—28—redistrict at the federal congressional level by having state legislatures draw and pass maps as regular legislation. Seven states involve an advisory commission in this legislative process. The plans must be approved by a simple majority vote in each chamber (except Nebraska, which has a unicameral legislature) with the exception of Connecticut and Maine, which require a 2/3 majority, and Ohio, which requires a 3/5 majority (including the approval of at least half of the minority party).

As with state legislative redistricting, most states—28—redistrict at the federal congressional level by having state legislatures draw and pass maps as regular legislation. Seven states involve an advisory commission in this legislative process. The plans must be approved by a simple majority vote in each chamber (except Nebraska, which has a unicameral legislature) with the exception of Connecticut and Maine, which require a 2/3 majority, and Ohio, which requires a 3/5 majority (including the approval of at least half of the minority party).

Four states use political appointee commissions to draw new maps and an additional four states use an independent commission.

Note that seven states do not need a federal legislative redistricting procedure as they currently have only one congressional district due to their small populations. It is, of course, possible that the upcoming Census could find that some of these states’ populations have increased enough to award them a second district. Several of these states, however, have never had more than one congressional district, and thus have never had to redistrict at the congressional level, leaving them without clearly defined plans in the event they are awarded a second district.

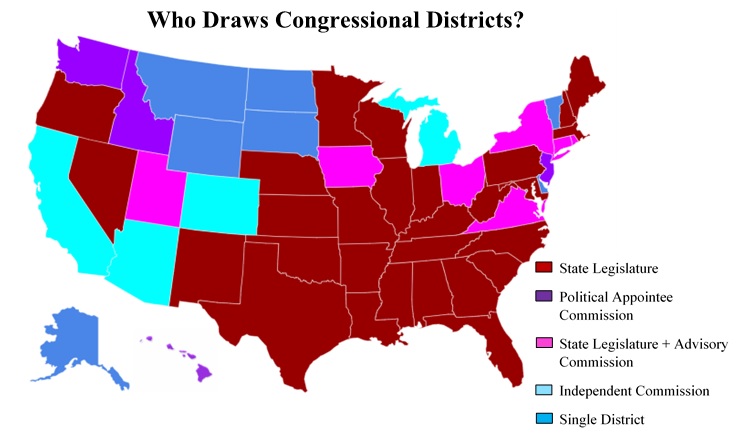

Gubernatorial Veto Power

Governors have veto power over state and federal maps approved by state legislatures in 31 states. Each of these 31 states pass maps as regular legislation. Some states, however, have different veto rules for state maps than for federal. In seven states, the governor has veto power over congressional maps but not for state legislative maps. Three of those states—Florida, Mississippi, and Maryland—expressly deny the governor the power of veto over state districts by law, while Arkansas, Missouri, Ohio, and Pennsylvania use different approaches for federal and state maps. Those four states use the legislature for federal maps but a non-legislative system for passing state maps, making the veto power irrelevant at the state level.

Governors have veto power over state and federal maps approved by state legislatures in 31 states. Each of these 31 states pass maps as regular legislation. Some states, however, have different veto rules for state maps than for federal. In seven states, the governor has veto power over congressional maps but not for state legislative maps. Three of those states—Florida, Mississippi, and Maryland—expressly deny the governor the power of veto over state districts by law, while Arkansas, Missouri, Ohio, and Pennsylvania use different approaches for federal and state maps. Those four states use the legislature for federal maps but a non-legislative system for passing state maps, making the veto power irrelevant at the state level.

In 10 states, the governor has no veto power over state or federal maps because the legislature does not play a role in passing the maps.

Finally, in North Carolina, while the legislature does pass both state and federal maps as regular legislation, the governor is expressly denied veto power over those maps.

Drawing Backup Maps

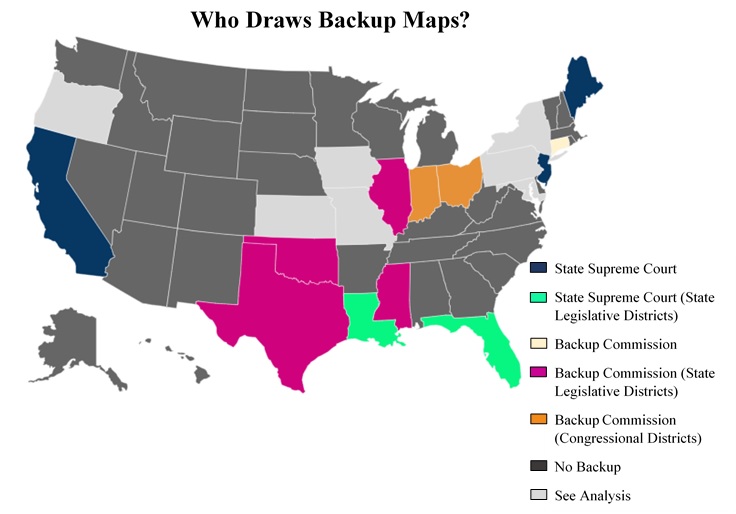

In the (relatively common) event that the body responsible for redistricting in a given state cannot come to an agreement on a map, many states have opted to have a backup plan. State Supreme Courts are charged with drawing backup maps in California, Maine, and New Jersey for both state legislative and congressional maps and in Florida and Louisiana for state legislative maps only. In California, after final maps are approved, they are voted on by the public via referendum. If a map is overturned by the public, the California Supreme Court must appoint a committee to draw a new map. Backup commissions are called on to draw maps for both state legislative and congressional districts in Connecticut, for state legislative districts only in Illinois, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Texas, and for congressional districts only in Indiana and Ohio.

In the (relatively common) event that the body responsible for redistricting in a given state cannot come to an agreement on a map, many states have opted to have a backup plan. State Supreme Courts are charged with drawing backup maps in California, Maine, and New Jersey for both state legislative and congressional maps and in Florida and Louisiana for state legislative maps only. In California, after final maps are approved, they are voted on by the public via referendum. If a map is overturned by the public, the California Supreme Court must appoint a committee to draw a new map. Backup commissions are called on to draw maps for both state legislative and congressional districts in Connecticut, for state legislative districts only in Illinois, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Texas, and for congressional districts only in Indiana and Ohio.

Other states have more specific and unique methods for drawing backup maps:

Iowa: If the first maps drawn by Iowa’s Legislative Services Agency (LSA) are not passed by the legislature, the LSA is given the opportunity to draft a second proposal. If that proposal also fails, the LSA drafts a third proposal. If the third proposal also fails, then the LSA is given the authority to pass its own maps without legislative interference.

Kansas: If the state legislative map (passed by the state legislature) is overturned by the Kansas Supreme Court, the legislature may attempt to redraw lines.

Maryland: The governor proposes a backup state legislative map that takes effect if the legislature is unable to come to an agreement.

Missouri: The state demographer proposes a backup state legislative map that becomes law unless the political appointee commission amends the map via a 70% vote.

New York: The state legislature may amend maps proposed by the advisory commission if it votes the maps down two times.

Oregon: If the state legislature is unable to pass a map, Oregon’s Secretary of State is responsible for drawing the state legislative map only.

Pennsylvania: If the first 4 members of the political appointee commission are unable to select a fifth tie-breaking member to serve as the commission’s chair, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court must appoint a chair.

Special Gubernatorial Powers

The following is a list of special gubernatorial powers by state, as they relate to redistricting. States that do not appear on this list do not provide their governors with special redistricting powers.

Alaska: The governor directly appoints two out of five commissioners on the political appointee commission.

Arizona: The governor, along with a 2/3 vote in the Arizona State Senate, can remove a commissioner from the independent commission “for substantial neglect of duty, gross misconduct in office, or inability to discharge the duties of office.”

Arkansas: The political commission charged with drawing state legislative maps is comprised of 3 members: the governor of Arkansas, the Arkansas secretary of state, and the attorney general of Arkansas.

Indiana: The governor appoints one of the five members of the backup commission. The backup commission is for the congressional district map only.

Maryland: The governor submits a state legislative redistricting proposal. The governor is assisted by an advisory commission that is appointed solely by the governor.

Missouri: For state legislative redistricting, there are two political appointee commissions, one for the state senate and one for the state house of representatives. For the senate redistricting commission, the state committee of each major party chooses 10 nominees from which the governor chooses five per party, for a total of 10 commissioners. For the house redistricting committee, the congressional district committee from each major political party nominates two members per congressional district, for a total of 32 nominees, from which the governor chooses 16 commissioners.

Ohio: The state legislative redistricting commission consists of seven members, one of whom is the governor. If the legislature fails to adopt a new congressional map, a seven-person backup commission, one of whom is the governor, will be formed to adopt a map.

Oklahoma: The governor appoints one Democrat and one Republican to the backup commission, if necessary. The backup commission is for the state legislative map only.

Utah: The governor selects the chairperson of the advisory commission.

Vermont: The governor appoints one member from each political party to the advisory commission. Each commissioner then appoints another member.

Virginia: In 2011, Governor Bob McDonnell created an advisory commission by executive order. This advisory commission is appointed solely by the governor.