Governor Richard Hughes and the Newark Report

Governor Richard Hughes’ Select Commission for the Study of Civil Disorder in New Jersey: Looking Back 50 Years

by Kristoffer Shields, March 2018

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the release of the findings of the study commission formed by then-Governor Richard J. Hughes in the wake of civil disorders in Newark and several other New Jersey cities in July 1967. The group’s analysis was prescient and merits revisiting now.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the release of the findings of the study commission formed by then-Governor Richard J. Hughes in the wake of civil disorders in Newark and several other New Jersey cities in July 1967. The group’s analysis was prescient and merits revisiting now.

On August 8, 1967, Governor Hughes officially announced the creation of the Governor’s Select Commission for the Study of Civil Disorder in New Jersey, which would come to be known as the “Lilley Commission,” after its chairman, New Jersey Bell

Telephone C.E.O. Robert Lilley. In February 1968, after six months of investigation, interviews, and document review, the commission issued its final report—a nearly 200 page document with analysis and policy recommendations.

The ultimate impact of the commission and its report is up for debate. While it led to multiple investigations of local government corruption and a number of its recommendations were adopted, many others languished. Eventually many joined the late historian Clement Price in concluding that it was, unfortunately “all but forgotten.”[i]

But the Lilley Report should not be forgotten. By chance, as the 50th anniversary approached, I became an accidental first-time reader of the report. A friend of the Center on the American Governor who is working on a biography of Raymond A. Brown (whose career included service as Vice-Chair of this commission) sent us a copy, thinking we might be interested in Governor Hughes’s decision to name two former governors to the commission.

But the Lilley Report should not be forgotten. By chance, as the 50th anniversary approached, I became an accidental first-time reader of the report. A friend of the Center on the American Governor who is working on a biography of Raymond A. Brown (whose career included service as Vice-Chair of this commission) sent us a copy, thinking we might be interested in Governor Hughes’s decision to name two former governors to the commission.

Reading the report in 2017/2018, I was struck by how moving and devastating its words remain. It is in some ways—particularly in choice of some of its language—rooted in its time, but in so many more ways it is still startlingly relevant to numerous current local and national challenges, particularly the remaining stains of racial discrimination. It is also a shining example of how gubernatorial commissions—though often maligned—can produce lasting and valuable work if we are willing to listen.

As the state’s chief executive, a governor inevitably performs a number of public roles. One of the most important and unpredictable is to respond in times of crisis. These are moments when a governor can rise above – or at least depart from – the party platform and inaugural agenda that accompanied him or her into office.

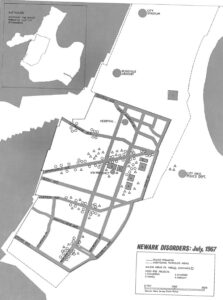

In August 1967, Governor Hughes, a year and a half into his second term, stood at such a crossroads. Just one month earlier—from July 12 – 17, 1967—the state had experienced a series of violent uprisings, most prominently in Newark, its largest city. With 26 dead and over ten million dollars in property damage to residences and small businesses, both the City and the entire state needed to know what had happened and why. As Hughes put it at the time, “The aftermath of this deeply troubling eruption gives rise to a fixed determination that never again, if it is within our capacity to prevent it, shall such a tragedy occur.”

In August 1967, Governor Hughes, a year and a half into his second term, stood at such a crossroads. Just one month earlier—from July 12 – 17, 1967—the state had experienced a series of violent uprisings, most prominently in Newark, its largest city. With 26 dead and over ten million dollars in property damage to residences and small businesses, both the City and the entire state needed to know what had happened and why. As Hughes put it at the time, “The aftermath of this deeply troubling eruption gives rise to a fixed determination that never again, if it is within our capacity to prevent it, shall such a tragedy occur.”

Defining what had happened and how similar future events might be prevented would not be simple. The protests and ensuing violence in Newark began after reports of police brutality against an African-American taxi driver pulled over for a traffic violation. But the causes of the unrest went much deeper, rooted in years of racial discrimination, neglect, and corruption. A complete review of what had happened—and what had exacerbated the situation—would require serious and uncomfortable questions about the actions of city officials including Newark Mayor Hugh Addonizio, the Newark police, the State Police, and Governor Hughes himself.

Three and a half weeks after the violence ended, amidst continuing debate and discussion, Governor Hughes announced his decision to appoint the Lilley Commission to raise and attempt to address these complicated questions.

The composition of the commission would be crucial to giving it the skills and credibility to accomplish its complex goals. Among those selected by Hughes were a number of prominent New Jerseyans, including the two governors who had directly preceded him, Alfred Driscoll (R, 1947-1954) and Robert Meyner (D, 1954-1962). One was a Democrat and one a Republican and together they had led the state for 16 years. Their presence lent the commission political heft that would be apparent to all and also, perhaps, help set a precedent for former New Jersey governors to remain engaged in state policy—a tradition that Governor Hughes and most of those who have followed him have continued to this day.

At least as important, the commission also included members of the Newark community, among them prominent African-American attorney Raymond A. Brown, who served as the vice-chair, and Oliver Lofton, an African-American attorney who had represented John Smith, the victim of the beating by Newark police that had set the tragic events in motion. Finally, the choice of the commission staff’s executive director proved to be crucial: former federal prosecutor Sanford Jaffe, who would pursue the inquiry with the experience and mindset shaped by his years of professional prosecutorial experience.

In February 1968, six months after Governor Hughes created the commission, it was ready to release its report. To the surprise of some, the report not only described the group’s investigation of what happened in Newark, Plainfield, and Englewood in July 1967, but it also provided a 100-page review of the structural conditions that had led to the violence, including (among others) sections on failures in the public school system, housing and employment discrimination, and police and government corruption.

In February 1968, six months after Governor Hughes created the commission, it was ready to release its report. To the surprise of some, the report not only described the group’s investigation of what happened in Newark, Plainfield, and Englewood in July 1967, but it also provided a 100-page review of the structural conditions that had led to the violence, including (among others) sections on failures in the public school system, housing and employment discrimination, and police and government corruption.

We at the Center on the American Governor mark the 50th anniversary of the release of the Lilley Report by highlighting it as an example of a governor’s use of gubernatorial power during a time of crisis, but also as a reminder of how deep-seated and enduring many of the issues it discusses remain.

The full text of the report (and transcripts of many of the proceedings) is available online via the Rutgers University Law School. For more information on the report and Newark in the summer of 1967, see the resources below.

All images of Newark are from the Lilley Commission report. Images of the governors are from the New Jersey State Archives, Department of State. Click to enlarge.

[i] It was, perhaps in part overshadowed by the federal “Kerner Report” released the following month. That report, commissioned by President Lyndon Johnson and led by another former governor—Otto Kerner of Illinois—also provided a thorough analysis of the root of violence in urban settings around the country in 1967. It became the most commonly-cited report on American urban violence in the 1960s. Clement Price quote from “Newark Remembers the Summer of 1967, So Should We All.” The Positive Community: July/August 2007.

Resources

Much has been written about the Newark uprising in 1967 as well as about the Lilley Commission itself. Ten years ago, in February 2008, the Rutgers Institute on Ethnicity, Culture, and the Modern Experience held an event commemorating the 40th anniversary of the commission’s report titled, “We Should Have Listened: The 1968 Lilley Commission’s New Vision of New Jersey.” A number of resources were created for that event, which are also included below. We would love to hear from you if you have other sources to suggest for inclusion.

- Bibliography compiled by Jesse Nettleton of the Rutgers University Institute on Ethnicity, Culture, and the Modern Experience. This is a comprehensive bibliography of books, articles, websites, and other published works related to the riots and the commission.

- Lonnie Bunch. “The Pain and Power of Remembering: 40 Years after the Newark Riots.” Prepared for the 40th anniversary conference on the Lilley Commission.

- Clement Alexander Price. “Newark Remembers the Summer of 1967, So Should We All.” The Positive Community: July/August 2007. P. 20.

- Clement Price. “New Jersey and the Near Collapse of Civic Culture: Reflections on the Summer of 1967.” Hall Institute of Public Policy Research Essay.

Books

- Robert Curvin. Inside Newark: Decline, Rebellion, and the Search for Transformation. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2014.

- Tom Hayden. Rebellion in Newark: Official Violence and Ghetto Response. Vintage Books, 1967.

- Ronald Porambo. No Cause for Indictment: An Autopsy of Newark. Hoboken: Melville House, 1971. 2nd ed., 2006.

- John B. Wefing. The Life and Times of Richard J. Hughes: The Politics of Civility. New Brunswick: Rivergate Books, 2009.

- The Kerner Report: The National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. Introduction by Julian Zelizer. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016.