Governor Brendan T. Byrne Job Approval Ratings

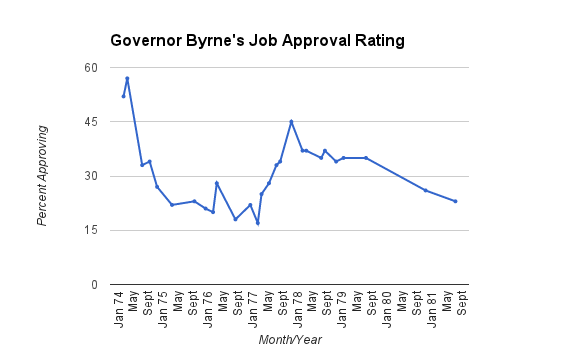

Brendan Byrne was elected into office in 1973 with what was then the largest landslide in New Jersey history. The perception of Byrne as “the man who couldn’t be bought” made him immensely popular at a time when faith in government, both federal and state, was at a low point, as the Watergate scandal still captivated the nation’s attention. New Jersey’s previous governor, William Cahill, had been defeated in his own party’s primary following accusations of corruption within his administration. Byrne’s huge victory also swept many Democratic state legislators into office, giving his party control of both chambers by wide majorities. Sixteen new Democrats entered the General Assembly and thirteen joined the State Senate. At a time when the country was mired in a negative atmosphere towards politics and politicians, Byrne projected an image of credibility and reliability, which led to a public approval of nearly 60% at the beginning of his first term.

The high approval did not last. In addition to the wide perceptions of corruption that Byrne was correcting, the state government also faced other serious challenges. The economy swung downward, eliminating jobs and erasing the budget surplus that many had expected to last. Robinson v. Cahill, a decision by the New Jersey Supreme Court in 1974, declared that the state was failing to provide the state constitution’s mandate of a “thorough and efficient” education for all students. Within that decision, the state was ordered to spend more money to improve the quality of education in the state’s poorest districts.

As the budget deficit grew in the face of a weak economy, growing unemployment, and a court order to increase state spending on education, Governor Byrne’s approval ratings slipped steadily. By the end of his first year in office, it had plummeted to about 20%.

The downturn in the Governor’s approval rating persisted through the midterm elections, rising only slightly to 23% in November 1975. Democrats in the legislature bore the brunt of growing discontent against the Governor’s administration, as 17 in the Assembly were defeated. The Democratic majority in the Assembly remained, but was weakened.

The major issue that caught the public attention became the need to commit additional dollars to education spending in response to the Robinson case. The Governor proposed a state income tax to pay for increased school funding, and signed the state’s first income tax into law on July 8, 1976. This, more than any other issue, turned the public against the Governor. Byrne, however, continued to argue publicly that, while nobody wanted the income tax, it was necessary to secure the state’s future.

For the next two years, Byrne’s approval ratings remained below 30 percent, giving the perception that he was vulnerable in his bid for reelection. Other Democratic candidates, sensing that the Governor could be defeated, announced their candidacy for the Democratic primary, and forced Byrne to first defend himself among his own party.

In June, just as the primary election was approaching, Byrne signed legislation opening Atlantic City to casino gambling for the first time. Just a few days later, in a crowded field that Byrne used to his advantage, he won the Democratic primary and was set him up against the Republican nominee Raymond Bateman in the general election. As the campaigns ramped up in June, polls put Byrne down by nearly 20 points.

Despite appearing likely to lose early on, Byrne fought back. He crossed the state, campaigning on the the need for the income tax, raising awareness of the initiatives he had supported, and the lack of alternatives his opponent was proposing. A key moment in Byrne’s reelection came when Bateman released his own economic plan that would eliminate the income tax. The plan was credited to former U.S. Treasury Secretary William Simon and called the “Bateman-Simon Plan.” Byrne latched onto the proposal, summing up the proposal as the “BS plan.” By raising doubts about the credibility of Bateman’s plan, Byrne turned the tide of the election, surged in the polls, and prevailed with nearly 55 percent of the vote.

At the beginning of his second term, Byrne’s popularity reached 45 percent, the highest it had been since the early days of his first term. Byrne continued to tackle controversial issues, such as regulating development of the Pinelands, advancing the development of the Meadowlands, and working to improve the state’s infrastructure. The public again began to disapprove of more of the governor’s actions, leading his approval ratings to again decline. In the middle of his second term, another 10 Democrats lost their seats in the General Assembly. By the time Byrne left office, his approval ratings had again sunk into the mid-20’s.

In the decades since Byrne’s term in office expired, his public opinion ratings have steadily increased. He is now remembered as a governor who was not afraid to tackle tough issues, and make unpopular decisions when they were in the best interests of the state. His proposals that were most controversial and unpopular when he was governor have over time become widely viewed as successful, garnering Byrne greater support. When Byrne left office in 1982, the his non-supporters outnumbered his supporters by a ratio of three-to-one. A decade and a half later, however, this had reversed, with a 1998 Eagleton Poll showing him with a two-to-one favorability margin. He is now remembered as one of New Jersey’s most significant and successful governors.